When I entered middle school a phase in Iran’s educational system that once existed between primary and high school my father bought me the first non children’s book of my life. It was Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev, the Russian author, a story of fathers and sons from two different eras, constantly wrestling and clashing with each other. I read a little, found it incredibly boring, and tossed it aside. For years, I wondered why he had chosen that particular book for me, out of thousands of possible titles.

Since my father, much like me (or rather, I take after him), rarely reveals the inner workings of his heart, we never spoke about his choice. Thirty some years later, when I asked him, he didn’t remember.

My childhood unfolded during the war. My father spent the entire duration of the conflict on the front lines. The image I had of him was that of an imposing colonel who would return home every few months. We’d visit the park or go to a restaurant, and he was always stern and serious.

When the war ended, my father now in his late forties seemed as though he had lost years of his life. He threw himself into work, channeling his focus into fulfilling professional ambitions. As a result, there was little opportunity for a warm, fatherly bond to develop between us. By that time, I had grown into a rebellious young man, and he had become an aging general whose mere introduction as “my father” intrigued me more than actually spending time with him.

Years have passed since then. My father is no longer driven by ambition. He spends his days with family, exercising regularly. I, too, have become a father and now experience the complex relationship between father and son.

I know I am overly lenient as a parent, and I’ve made no effort to become a stricter father. Perhaps this self indulgent approach to fatherhood stems from the wounds of my own childhood I don’t know.

But I think of that book. What was my father trying to tell me?

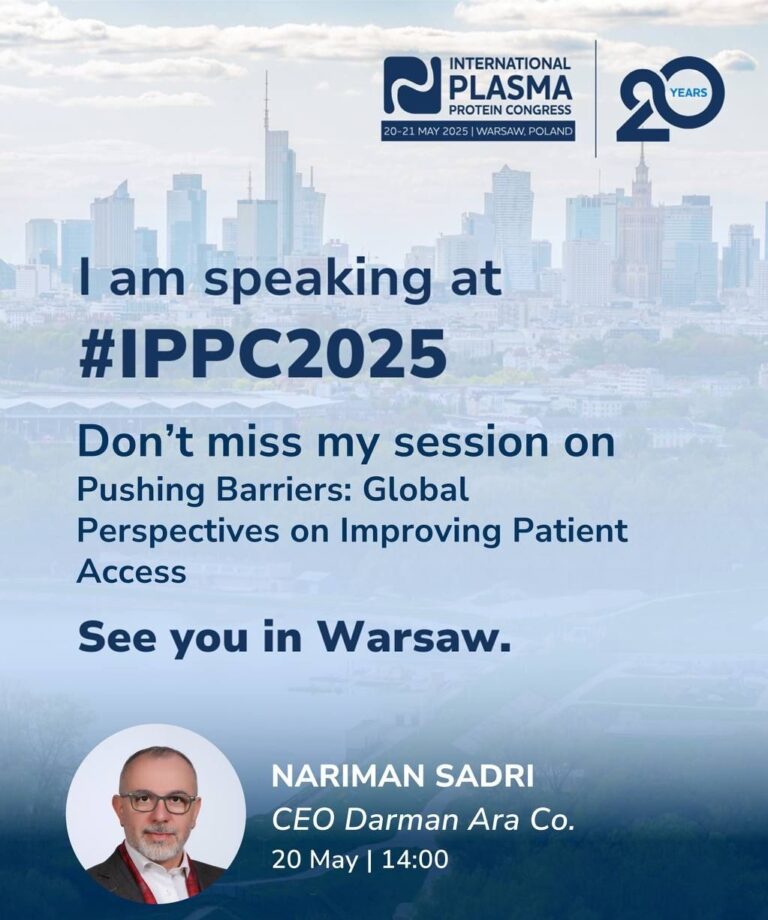

In my professional life, I now work alongside fathers slightly younger than mine. Every day, their conservative views clash with the radical ideas of my younger colleagues a constant reminder of the ideological divide between my father and me. Fathers represent the conservative, traditional figures in society, resistant to change or embracing it only reluctantly. Sons, on the other hand, are radical dreamers, driven by extreme ideas to reshape the world. This tension fuels the progress of humanity. Perhaps, one day, this same dynamic will emerge between my son, Sam, and me.

But beyond these differences, fatherhood is the embodiment of love. Even when we struggle to express it, a father’s love for his child reflects love for the next generation the desire to continue humanity’s evolution and pass on our genetic legacy to a future better than the world we know today.

My love for my child is a process through which I will age and empty myself while the next generation grows fuller and richer, continuing my story.

Fatherhood is humanity’s experience of immortality.

Through countless generations, fathers have lived this profound journey. But in the narrow alleyways of history, this experience compared to the revered and celebrated maternal love has often been distorted or overlooked. Perhaps its significance can only be deeply understood once you become a father yourself.

I am reminded of the Iranian film The Glass Agency and the scene where Haj Kazem arm wrestles his son through the bars, ultimately letting his son win. These days, when my father and I argue, he lets me win. This man with whom I have sparred endlessly now looks at me with eyes that laugh kindly.

And I know that one day, I will let Sam win too.