From the time when some collective activities in school were assigned to the students themselves – such as putting up the flag and decorating classrooms for the Ten-Day Dawn celebrations – it was always important to me to form groups with my classmates and decide together what tasks we should take on. Back then, I was often chosen to be the class monitor, and I always felt torn between representing my classmates or the school disciplinarian. A certain anarchistic feeling led me to represent my friends – it somehow felt more right – and I enjoyed the popularity it brought me among my peers. Sometimes, however, I paid the price for it. I was punished during military training classes for the chaos we caused, and my conduct grade suffered after we brought firecrackers to school for Chaharshanbe Suri and hid them.

Later, at university, I became a student representative and had to confront some of the strict standards of the time. However, the traditional system before the reform era did not tolerate a young troublemaker like me.

Almost everywhere I have had the chance to participate in group activities and amplify the voice of my peers or my class, I have eagerly taken part in collective movements – from voting for labor union representatives to running as a candidate or collaborating with those elected.

Today is the Medical Council election, and for the past few days, I have left a piece of paper on the kitchen counter to list and review the candidates – most of whom are unknown to me. In the analyses I have read about past elections, I discovered that only a small percentage of doctors actually participate in the voting process (about 15-20%). This number struck me as odd because, despite being distanced from medical practice, I engaged in this process with interest. I decided to do some research on the topic and read several analytical articles about voting behavior. The simplified conclusion of these articles is:

The demographic factor most strongly correlated with voting is the level of education. However, in the case of the Medical Council elections, this did not help much since the voters are all highly educated. Regarding the reasons for not voting, voter fatigue from fruitless elections with no positive feedback is the primary cause of non-participation. Based on my review of past Medical Council elections, this could be a factor, but not the main one, as low participation has always been a trend, and there has been little indication that voting differently would lead to any tangible change.

The second reason is voter alienation from the candidates and a lack of intellectual and emotional connection. In my opinion, this could be very relevant to these elections. The eligibility process effectively disqualifies a large portion of doctors from running – many of whom closely resemble the general medical community. Meanwhile, the remaining candidates represent only a segment of the medical profession, not the whole. My personal experience supports this observation, as I struggled to compile a list on that piece of paper. Many of the respected candidates do not represent the majority of the medical community I have known for years.

In any case, I will cast my vote, hoping that those elected will prioritize creating more opportunities for participation in the future.

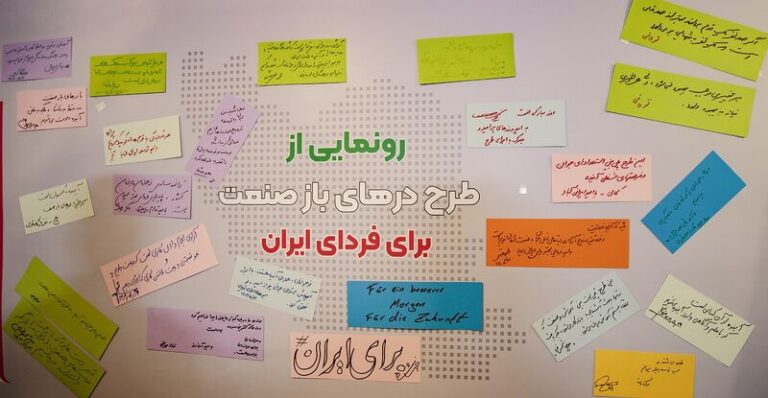

Photo: Fourth Congress of Iranian Physicians in Ramsar, 1955.