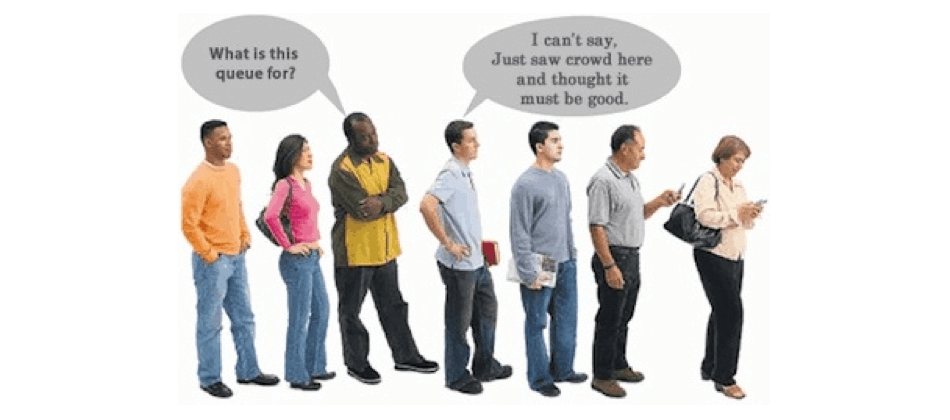

The principle of social proof works in humans in such a way that we perceive something as correct when it is approved by others in society. If a behavior is exhibited by others in a specific context, we tend to think it is the right thing to do, and conversely, behaviors that others do not engage in appear wrong to us.

The nature of social proof and the tendency to follow social behaviors and reactions without deep thinking is simultaneously the strength and weakness of this deeply rooted principle in us. While it often leads to social convergence, where behaviors align within a culture and bring a tribe or nation closer together, its reactive nature is also its weakness. It can be manipulated to encourage us to engage in incorrect behaviors.

The problem arises when social proof is exploited, and a group falls into the trap of fraudulent social proof. News agencies aligned with political groups often take advantage of this technique. A demonstration, which is a verifiable event with, say, one hundred thousand participants, is broadcast live on a news channel supporting the political movement of the demonstrators. The camera angle shows a large crowd, and the reporter claims that a million people attended. Naturally, most of the network’s viewers, who align with that political movement, think, “Wow, we are falling behind; we should join this million person crowd,” and eventually convince themselves that they are part of the righteous majority. On the other hand, a news channel opposing the political movement might film the demonstration in such a way that the crowd appears scattered and small, reporting that only ten thousand people participated. Their viewers, who do not align with the demonstrators’ political movement, would then consider them to be the absolute minority.

In the business world, I saw the impact of social proof in the story of the Tehran stock market over the past year. When the stock market was experiencing daily growth, I gathered all the energy of my knowledge to explain to my friends that this kind of growth in a market doesn’t work and is a bubble. I felt very confident, thinking I was explaining to them that such investment and betting was wrong. But to my astonishment, I saw that not only was their analysis of the stock market bubble the same as mine, but they even had numerous examples of other market bubbles they could cite in detail. Yet, they still believed the market would not crash because they had the collective belief, reinforced by social proof, that the government would prevent a crash by intervening in the market and manipulating it. This collective movement toward the stock market went so far that the state run television broadcast a story about a village where farmers had put aside their work to buy and sell stocks, and they were quite successful. As a result, entering the stock market became a popular and accepted way to build wealth in every family. Social proof and the mass movement toward the stock market, despite the government’s intervention to reduce damage, ultimately resulted in one of the biggest crashes in investment history in Iran.

To avoid the trap of social proof, it is essential to always be alert and recognize deceptive signals. This is not easy unless we practice, even in instances where our collective behaviors seem right, to ask ourselves why. Will my participation in a group behavior, which is not based on my own deep thinking about the issue, align with my individual judgment? If I think deeply about the underlying value of my behavior, will it still make sense?

We should challenge ourselves to evaluate how much of our imitative behavior aligns with our own reasoning.