Since the beginning of the year, the allocation of government currency for the supply of medicine has been the most challenging issue for the industry. Last week, an analytical report from one of the country’s non-specialized news agencies was published regarding the allocation statistics, which included several key points. Firstly, 45% of the total allocated currency, approximately 59 million euros out of the 131 million euros allocated, was assigned to a few limited companies. Most of it was allocated to a category of medicines used for rare diseases. The report concluded that there is a lack of transparency in the allocation process, and oversight systems must intervene to direct currency resources toward supplying the medicines needed by the general public. The bitter irony of the situation is that even the policymakers responsible for these allocations attribute the issue to the existence of a “medicine mafia.”

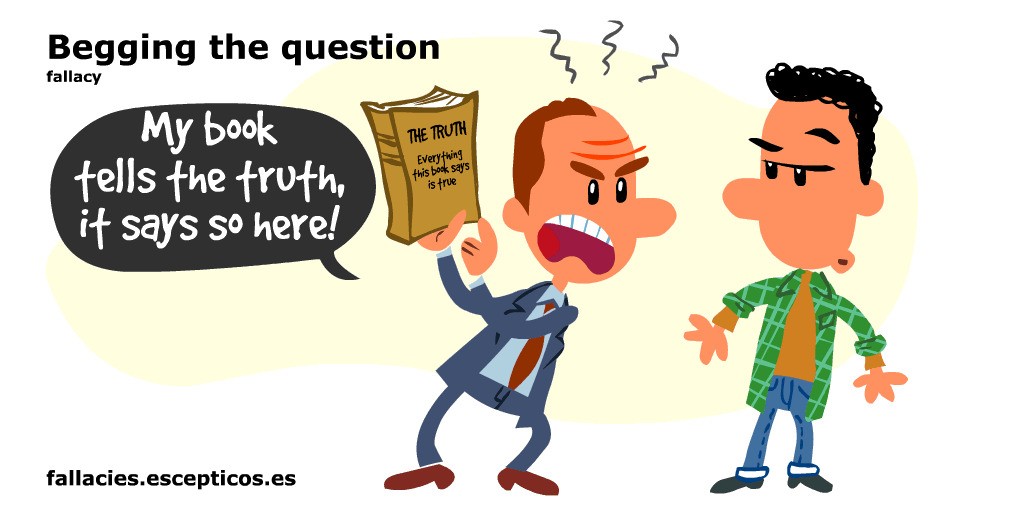

The fallacy of “begging the question” (circular reasoning) is one of the most common types of fallacies. This fallacy is prevalent even among experts, scientists, and logicians. It occurs when a conclusion that one desires is drawn based on assumptions that are either true or appear to be true.

In the past two years, the goal-setting process to reduce foreign currency expenditure in the pharmaceutical industry has diverged from existing realities. For months, the necessary currency for importing medicine for patients with rare diseases was not provided. Therefore, it is natural that when pressure mounts and shortages arise, compensatory actions must be taken to address past mistakes. This often means allocating funds and importing a year’s supply of medicine within three months. (It should be noted that the total allocated currency in the last three months has been one-fifth of the industry’s needs.) However, some policymakers deliberately use the fallacy of “begging the question” to obscure the crisis they created through poor decision-making, attributing the cause of the crisis to ambiguous and unknown entities like the mafia, rather than their own incompetence.

In the fallacy of begging the question, an unproven and assumed premise is taken as certain and used to justify conclusions that require further evidence. While there is no doubt that corruption exists within our bureaucratic and complex administrative system – and many of us can cite numerous personal experiences and solid evidence of administrative corruption – this assumption does not absolve decision-makers of their responsibility to act wisely and competently. This approach, where even senior policymakers evade accountability for their poor decisions by blaming vague entities like mafias or so-called “sultans” of particular sectors, will not resolve the problem. Ultimately, such circular reasoning perpetuates the presence of incompetent individuals within the decision-making system.

Do you remember the numerous “sultans” arrested or the various mafia networks dismantled in recent years? Which economic problems were resolved as a result? While expediting the establishment of transparent decision-making processes is essential to reduce administrative corruption, selecting competent managers is even more critical to ensure that incompetence is not concealed behind the facade of fictitious giants.

(The graphic is used with permission from the website.)