This past week, my colleagues and I spent a great deal of time re-planning the supply of a critical drug. Two months ago, based on market analysis, we predicted a shortage and repeatedly wrote to the government official responsible for approving its import. Despite numerous attempts to convince him, every meeting ended the same way – he would cut us off mid-sentence with a bored expression, confidently asserting that he had reviewed the situation and no shortage was imminent. Eventually, the shortage happened, and the relentless pressure from that same official followed – demanding immediate action to secure the supply.

“COVID will end by spring. We are implementing the best pandemic management model. Masks don’t prevent the spread of COVID…” – these were the confident statements made by health officials in a country that experienced five severe waves of the virus. We weren’t the worst, nor the best in managing the pandemic. By looking at global data, we realize that in very few areas can we use the superlative “-est” to describe ourselves – whether positively or negatively. Yet, we seem to love using superlatives. In our official rhetoric, we analyze the world around us as if there is only one reality – ours, and the truth belongs solely to us.

Since the start of the week, I had been carrying a sense of frustration – why do government officials cling to their analyses with such unfounded confidence? But after a few events at work, that frustration transformed into an opportunity for reflection.

In a corporate meeting among senior managers of a private group, one manager passionately spoke about a market reality. Based on his personal experiences – rather than verified field data – he recommended significant investments. A simple search revealed his analysis was fundamentally flawed. In another event, during a startup gathering, an entrepreneur enthusiastically defended an idea. When I tried to challenge his hypothesis from a different perspective, the conversation abruptly ended without resolution. He proceeded with his idea regardless – perhaps it will succeed, but I realized there was little room for opposing viewpoints.

Maybe this isn’t just a government problem.

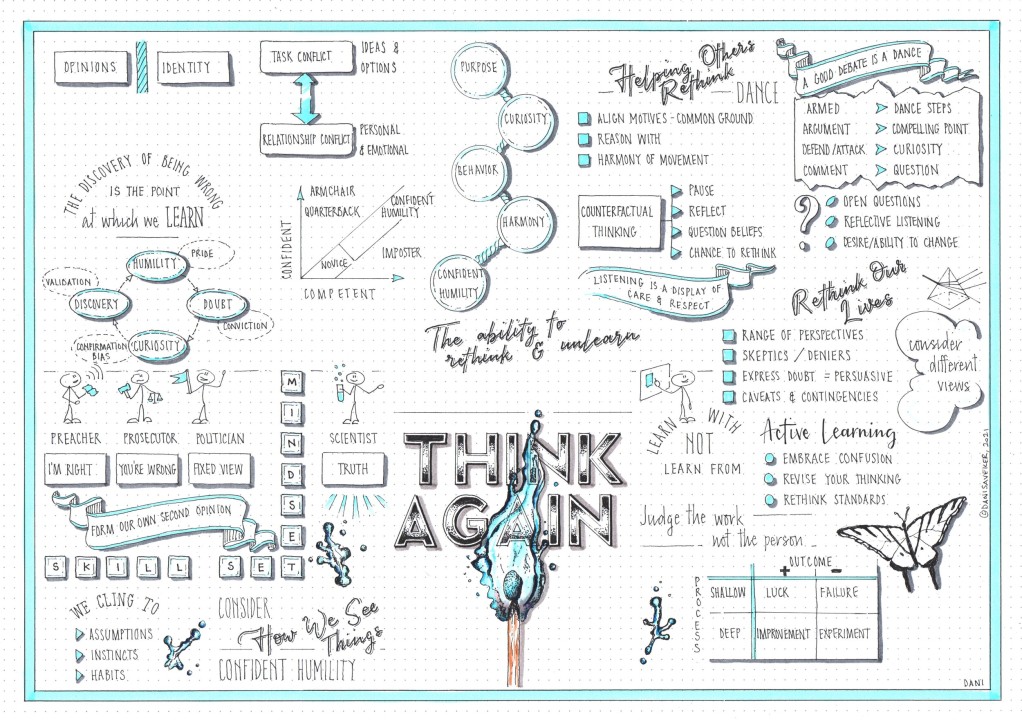

I was fortunate that in the same week, while reflecting on “the power of knowing what we don’t know,” the world presented me with a unique learning opportunity – the book Think Again by Adam Grant. The core idea of this book revolves around reconsidering our beliefs and assumptions, helping us avoid falling into our own mental traps.

Adam Grant highlights the significant issue of belief bias – something that can cause irreparable harm in both our professional and personal lives.

By conventional definitions, intelligence is the ability to think and learn. Most people assume that being more intelligent allows them to solve more complex problems and find solutions faster. However, in today’s complex world, a different set of cognitive skills might be even more crucial – skills like rethinking, reconsidering, and unlearning old beliefs and knowledge.

The book centers around one critical question: “I believe something – but what if I’m wrong?”

There are valuable insights in the book on active listening. Often, we listen to “win” a conversation – while someone is speaking, we are already formulating our response. Our inner speaker eagerly prepares a sharp reply, our inner prosecutor focuses on dissecting the flaws in the speaker’s argument, and our inner politician uses tricks and tactics to defend our old beliefs. At that moment, we need an inner scientist to remind us that we might be wrong. This inner scientist challenges our overconfidence and reminds us that truth lies outside of ourselves.

The book teaches us that changing our beliefs is not a flaw. Even the most entrenched convictions can shift. The reality is – we don’t know what we don’t know.

Reading this book might shine a light on your path as well. I’ll stop here, as only Adam Grant can do full justice to the topic.

Photo used with the author’s permission from www.visualsynopsis.com.